Gillian Beer

I realise that what I present here is necessarily brief in terms of summing up of both the provocations and the conversation afterwards. I am also intensely aware it must contain a good deal of my own thoughts, but that these thoughts might have been articulated by others in different ways. The sessions begin at 9:30 with the first provocation. There is a coffee break at 11:00, which is followed by the second provocation.

Gillian Beer's provocation concentrated on the writer-reader relationship and investigated the differences between memoir and fiction. She postulated a resistant reader and reminded us that the idea of the contact between writer and reader is not automatically available.

The reader of the memoir, she said, ‘has no part in the conversation’ - what is happening is happening to a written ‘them’. The reader has to trust that what they are told really did happen as described. The distance between reader and text or author is implicit. The author may be wanting to offer us a particular reading of his or her life. We think of the celebrity memoir.

[But why should we be interested in the lives of others? Why spend time reading about others in general and one specific other in particular? There are people in whom we have some kind of interest and that may, for some, involve celebrities. On the other hand, we may feel a twinge of guilt in such 'nosiness' especially when tragedy is involved. I think of the so-called 'ghouls' at the scene of a wreck. I think of Warhol's Crash series. I think of our interest in the dead generally.

Such things are dramatic of course. But what do we seek in less tragic lives? Why are we drawn to examine them and seek the further evidences of diaries, letters and archives of scribbled notes, cards, lists? Curiosity is natural. Without curiosity there would be no human progress, no human interest, certainly no literature or any other art?

But what do we seek in memoir in particular, where the author gives a personal account of not only the events through which he or she has passed, but also the personal feelings nd thoughts associated with it? In what way is this presentation of reality as personal evidence different from other possible forms. Is autobiography different? Is the story told round a table different?]

While memoir is in some sense a 'closed' form, suggested Gillian, fiction is 'open'. The reader enters as a participant [I wanted to know more about the way the reader participates and whether memoir was quite as closed as a straight contrast sugsests], unfettered by the likelihood of things actually happening or having happened. Here we discover a different kind of belief but may also reject it by abandoning the book. Why might we do that? Is it because we don’t like the development or is it because of some factor in the narrative that we find difficult to accept? Because it betrays us in some way, breaking the trust we have placed in it?

[I kept thinking of context and convention here. Is it the proprieties of the convention that induce trust? Do we accept such conventions as the frame within which the contract between writer and reader may be established. Does loss of trust occur because the book has, in some way, broken the frame? Or could it be precisely because it has kept to comfortably in the frame, the frame being something about which we are - rightly? - sceptical. Life is not to be too easily framed. Framing, we might argue, is cliché.]

The conversation moved this way and that. Does memoir refer to an essentially locatable self? How far is that self locatable? Teju Cole questioned the standard definition of memoir. Alvin Pang wondered if memoir, given time, might become fiction. Cathy Cole talked about scepticism regarding the reality of the self. Robin Hemley quipped that the first novel was in fact often taken to be a form of memoir.

The credibility of memoir [but possibly of fiction too?] might be a matter of detail, suggested Gail Jones, a matter of detail and recapitulation. She talked of the moment of authentic feeling. Perhaps authentic feeling was what we really wanted, I added, or maybe authentication of feeling, that truth in this sense was that kind of creature. Joe Dunthorne talked of 'truthiness' - a term he thinks he read in Luke Kennard, and I first heard on R4 the other day. What was it? I said I understood it as the system whereby the listener / reader is given the impression that the speaker /writer believes so firmly in what they are saying that the listener / reader is obliged to give it some credence. (George Bush was mentioned in this context.)

On the matter of detail, it might have been Robin who told us that Marquez had written a scene where a room is filled with butterflies and, realising that this sounded merely fanciful, added yellow butterflies to make it convincing.Incidentally, Robin informed us, he taught a semester on fake memoirs at Iowa. Very popular too. There are of course a good number of examples, including some Holocaust memoirs. These books might still be good books, he added , and some of them recover critical respectability. The authentic, the true, and the facts are not necessarily the same.

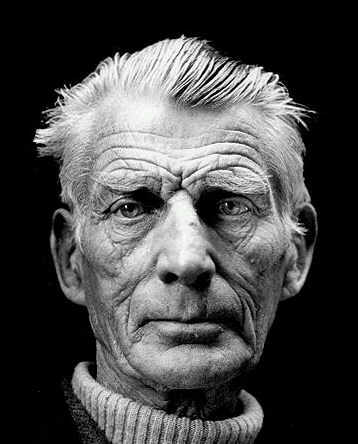

Tim Parks suggested the self as a position in both life and narrative,and how hard it was to find such a narrative. He referred to Beckett's First Love and how the homeless figure demands everything and gives nothing, exactly as Beckett himself did in service of his art.

There was then the dilemma of a potentially longed for, or required misreading in poets such as Christopher Reid's Katerina Brac (the invented poet), or indeed the question of poetry as a reporter of memoir events. Christopher Reid and Jo Shapcott's Costa Prize winning books, Reid's book, A Scattering, being about the death of his wife, Lucinda; Shapcott's Of Mutability about her own grave illness. Perhaps poetry was deemed to tell us more, or give us more understanding of personal history under stress.

John Coetzee's provocation follows.

1 comment:

in 'After Confession: Poetry as Autobiography", the American poet Ted Kooser takes a position that it is "despicable" not to tell the factual truth in a first person poem unless the poet somehow also signals to the reader that the poem is fiction. He says he feels it is the poet's duty to "in some way advise" the reader "that the experience presented may not be the poet's own." (his essay is titled "Lying for the sake of making poems").

This seems to me to be a very odd position to take; students are encouraged to leave behind 'but that's what actually happened' in order to work on what the poem needs. For myself, like you, it is authenticity of feeling that matters and actual facts may need to be changed to serve the internal truth (or 'truthiness?) of the poem.

Post a Comment